Discovering one’s true calling is often an intricate and multifaceted odyssey, marked by pivotal moments of realisation, personal growth, and the courage to deviate from expected paths. For our guest today, Areesha Khalid, this journey began with an initial pursuit of a career in medicine, a path seemingly set by familial and cultural expectations. However, it soon became apparent that this was not a source of joy or fulfilment. This realisation sparked a transformation, leading to an unexpected yet rewarding foray into the realms of architecture and design. In this conversation, we explore how her upbringing and diverse experiences shaped this transition, ultimately culminating in a unique artistic practice that celebrates her South Asian heritage while challenging conventional architectural paradigms.

Navigating the complexities of identity and representation, especially as an immigrant artist, is a nuanced endeavour. She candidly acknowledges the sense of guilt that sometimes accompanies her romanticised depictions of South Asian heritage. Yet, this romanticisation is also a means of coping and celebrating the beauty and richness of her cultural roots. Her work strikes a delicate balance between personal introspection and broader cultural commentary, resonating deeply with those who share similar diasporic narratives.

As she looks to the future, her aspirations are as multifaceted as her journey thus far. Through these endeavours, she aims to continue creating art that resonates globally, bridging cultural divides and fostering a deeper appreciation for the diverse tapestries of human experience.

Could you walk us through your journey from considering a career in medicine to becoming an architect and designer, and how your upbringing and experiences influenced this transition?

I have always had a creative streak but after completing my A levels in 2016, I was set to study medicine (a somewhat predestined family path, as is the case with most brown families). But after years/months of prep and entrance exams, once I finally got there, it became quickly apparent to me that this was not the right path for me and was bringing me no joy at all. So, I quit medicine and started my bachelor’s in architecture at the University of Westminster that same year. I felt it would be a good way to stimulate both my scientific and artistic brain, besides that it was kind of a blind jump into the unknown for me but thankfully I really enjoyed it and it was the best decision I made! After 3 years of undergraduate studies, I worked as a Part I architectural assistant at a studio in London for a year and then started my masters again at Westminster in 2020.

Architecture for the most part is based on a very Eurocentric curriculum and within this curriculum for the first 3 years of undergrad I struggled to find my representation style. I was kind of trying to mimic what I was seeing or being taught, but it wasn’t really me. I was also new to London, having moved there from my very white-dominated, small, Suffolk town where I never quite fit in, being one of the only poc’s at school. However, having moved to London for uni and being surrounded by the most diverse groups of people in a melting pot of cultures, near the end of my undergrad, I was finally beginning to come to grips with my identity as a British Pakistani and accepting and celebrating both parts of this identity.

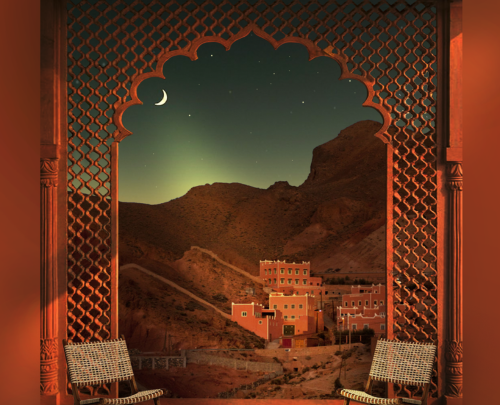

In 2020 when COVID hit and I was set to start my master’s soon and had some extra time on hand, I started creating my south asian spatial nostalgia art. It was kind of a physical/visual embodiment of me finally being not only fully comfortable but also very proud of my identity and South Asian heritage. It was a way to read up and learn more about myself and where I come from but also a way to navigate through my feelings of acceptance for my culture, which is expressed in my romanticised, nostalgic depictions of ‘home’. This newfound solidification in my identity also allowed me to pursue topics of my choice during my master’s, such as my thesis writing and my final year project which were both based on my South Asian heritage.

What motivated you to start ‘Diaspora Digest,’ and how does it differ from conventional architectural representations, particularly in terms of capturing South Asian spatial nostalgia?

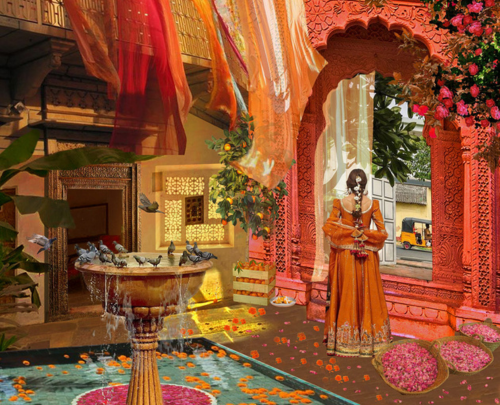

The first diaspora digest drawing I created was in June 2020. I always start with a narrative that informs the drawing, whether that’s a real story someone has shared with me or a specific cultural object/element/architectural feature that has inspired me to weave a narrative around e.g. a traditional outfit that stood out, a funky street sign in the local language, traditional floral tiles spotted in an old house’s courtyard, even a certain colour palette rich in traditional tones that I’ve seen somewhere on the street during my visits back home. I then form a mood board around my narrative using my own images from my annual Pakistan visits and images from the internet. After this begins the drawing process.

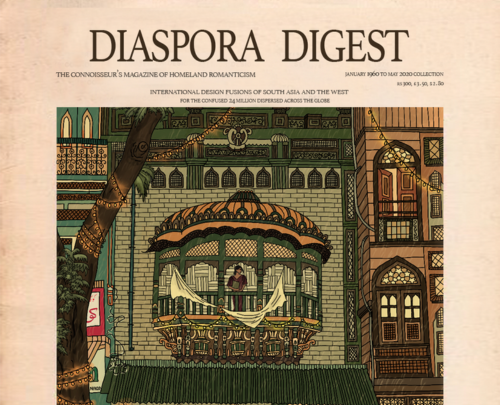

As for the title ‘Diaspora Digest’ I came across a vintage architectural digest cover from the 70s a few years ago and really liked the aesthetic of it. I noticed the depictions and text on it were specifically catering to a Western market. This was expected given that it was from the 70’s, architectural digest is now much more inclusive. But that cover read something like; “international interiors from homes: London, Athens, Montreal” so I just pinned that to “international design fusions of south Asia and the West for the confused 24 million dispersed across the globe”, “the connoisseur’s magazine of homeland romanticism”. I felt like it was a cool way to create a desi/diaspora club and to make us feel included and seen, I originally did not expect it to become an ongoing series and the title of my very own coffee table book, but as soon as the first one was released, there was so much love and appreciation for it so i kept creating more.

As most architecture and design enthusiasts I’ve always loved skimming through the new copy on the stands, but growing up, I noticed that an architectural digest was often a platform to highlight and appreciate the most pristine, curated and neat western homes. Which was not the reality for a lot of immigrant families, trying to simply survive in Western countries. The living rooms weren’t covered in lush greenery with coordinated cloud couches and fireplaces but instead, there was a cosy Persian carpeted room, almost overflowing with random trinkets collected over time, crowded by a sea of relatives and family friends at all times. It was home nonetheless.

The diaspora digest spin offered representation for not only more imperfect, familiar spaces but also traditional spaces.

How do you select the themes and influences for your illustrations, such as Islamic architecture, South Asian art, and interior design, and what significance do these elements hold for you personally?

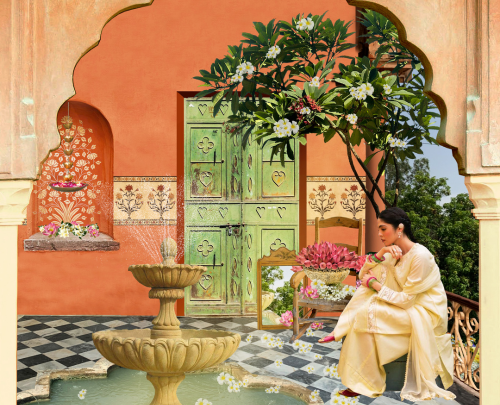

My work is a way of expressing my South Asian heritage and since the built environment and architecture are the line of interest set that comes naturally to me, I always root my work in key vernacular spaces to depict my heritage. I believe the spaces that we occupy tend to soak in the culture of the people that they house. Spaces can tell stories of people through colour, pattern, writing, signage, wear and tear and much more. Capturing this ‘lived-in’ quality of space is essentially what conveys the culture and heritage in my work.

Also, people sit at the heart of and dictate any culture, so first-hand research plays a big role in my work. Almost all my pieces are informed by either my own experiences back home or a local’s story or experience. Whether that’s a conversation with my mum about a certain memory from her childhood, embedded in the backdrop of specific spaces that I depict with my creative twist, hoping to convey the same emotions she expressed when telling me her story or something I read or see online about other’s stories.

I find that when someone is talking about a fond memory, it will often be embedded in a space which they are able to vividly recall, expressing minute, atmospheric details which hold sentimental or cultural significance and therefore have stuck with them. This could be the peace of shade provided by thick vines wrapping their balcony, the sound of splashing water in their courtyard fountain during the peak of summer, or the earthy scent of rain touching the dry soil of their backyard signalling the start of monsoon. I always like to highlight these details, as I feel they convey the essence of culture and nostalgia in my work.

Movies and music/music videos have also always played a huge role in influencing and inspiring my work. I have always been fascinated by Bollywood movies by the likes of directors such as Sanjay Leela Bhansali who often depicts historical South Asian landscapes in a romanticised, larger-than-life, grand, manner with architecture and set design often sitting at the centre of all his movies. In fact, set design and art direction is a long-time dream path that I am slowly trying to set foot into.

Your postcards are described as miniature canvases of diverse inspiration. Could you share the process behind creating these postcards and how you infuse them with cultural influences?

The postcards are basically miniatures of the large-scale prints so the same thought processes apply. I just love the idea of a handwritten letter posted to someone that they can cherish forever as opposed to a text! Definitely a lost art that I’d love to bring back.

The special edition postcard, ‘Taking care of you,’ is tied to a social cause supporting women’s health equity. Can you tell us more about the inspiration behind this project and its impact on your advocacy through art?

‘Taking Care of You’ is a book by Mayo Clinic USA. The author, Kanwal had been a long-time customer, she reached out to me last year with the idea for this illustration; a book she had spent 3 years writing! The first easy-to-use and comprehensive book on non-reproductive women’s health. Written with over 111 other female medical experts’ advice. She mentioned how she wrote this book because of her own struggles and seeing her immigrant mother going through issues in the healthcare system, not being able to advocate for herself etc as many of our mums in the global diaspora. So this book was her “love letter to every woman”. Hoping it will become a health equity tool, putting power back in the hands of women! The illustration very much tried to capture the essence of “love letter to every woman”, from generation to generation, passing the knowledge and power on.

I believe artists should always stand for something and use their art as a medium for betterment, for making statements, for speaking out in society, so wherever I can use my work to amplify causes and voices, whether that’s women’s public health equity or the vision for a free Palestine, I will always try my best to make my voice be heard using my art.

Your designs often reflect personal narratives and broader cultural themes. How do you balance the intimate aspects of your identity with the broader messages you aim to convey through your artwork?

The personal narratives will often be things the majority of the diaspora can relate to so this usually isn’t an issue. For example my autumn | khizan piece: was one of the first digital collage-style drawings I made as part of my south asian spatial nostalgia work. It was actually entirely based on a conversation with my mum. I remember it was the beginning of autumn here in England and the colour palette of the streets was slowly shifting to deep oranges, crimsons and browns and it was raining of course. Mum was recalling how she’d love to sit under the autumn sun outside with an entire carton of oranges to herself and peel and eat away while soaking the warm sun as the slightly cool breeze passes.

This was rooted in a childhood memory of hers where she would do exactly this in the courtyard of her childhood home in Pakistan every autumn. I heard this description of her memory, with its very vivid atmospheric details and reconstructed a warm, autumn image visualising this memory. Of course, I romanticised it using my creative freedom. Her courtyard was small and cosy and did not have a fountain but it did have a tree. I just wanted to create the most beautiful picture of this memory she held so close to her heart and was longing for. When I showed her the final image, she told me she felt so much nostalgia through the drawing, it almost felt like a romanticised painting of the memory in her mind.

Many can relate to this longing for home.

You have previously mentioned experiencing a sense of guilt as an immigrant artist drawing inspiration from your homeland. How do you navigate this complex emotional landscape in your creative process?

I do feel and admit that I am comparatively disconnected from my south asian heritage compared to a local since I no longer live there and only visit annually. I also am not directly impacted by all the negatives of living in Pakistan, that too, as a woman which comes with a multitude of disadvantages and hardships. This kind of provides me with a lens that is less blemished by these experiences, perhaps rose-tinted (which I feel the insane burden of with every visit back home). The disconnection actually forces me to see my south asian heritage with a bias of a kind, resulting in romanticised depictions of it.

I understand and recognise the issue with this and it’s something that I have struggled with wrapping my head around for quite some time now. But as people of the diaspora who are already struggling with their identity and some even battling acceptance in Western countries, I find many young people resonate with my work because it paints our culture in this warm, beautiful, positive light as opposed to the overwhelming drawbacks and injustices that come with most places/countries.

Whether I should see this as a positive for my work that brings the diaspora together or as ignorance on my end, is honestly an internal contradiction that I constantly battle with and struggle to communicate at the risk of sounding insensitive.

However, I do believe that there is power in the hybridity of my British-Pakistani identity, which allows me a new and fresh perspective on things. I try to keep educated about the struggles of those back home to keep myself informed and away from any risk of sounding insensitive / lacking empathy. But I will continue to create my romanticised depictions because it has perhaps become a coping mechanism at this point to deal with all that is wrong with my home country. The romanticisation in my work is somewhat self-aware and intentional rather than an Orientalist romantic depiction of South Asia. Mine is a means to self-exploration of the diasporic conundrum, and the acceptance of the separation between myself and my homeland.

The cover of “Diaspora Digest” showcases the streets of Old Rawalpindi, reflecting both warmth and guilt. Can you delve deeper into the emotions and themes conveyed through this imagery?

This was the first digital drawing I did on Procreate as part of the diaspora digest series. I drew it in June 2020, which marked my 11th year in England. I had spent exactly half my life (11 years) in Pakistan and half (11 years) in England.

So I sat down to draw a very traditional, old, androon Rawalpindi residential building which is my birthplace, to mark this occasion. But I unintentionally ended up with somewhat of an Asian/European fusion. It somehow dreamily represents past recollections of the city I was born.

A RIBA article commending this piece for the RIBA eyeline drawing commendation in 2021 described it as having an “almost child-like understanding of memory’’. At the time drawing was not something I was going for but it ended up being that way because perhaps my memories of the place I was trying to depict were all perceived from a child’s pov. I have since been working on sharpening up my research and knowledge on these buildings and my heritage etc by reading and visiting these spaces. But I have not been able to shake off this child-like, almost cartoonish style which I have actually grown to love!

Can you share any upcoming projects or initiatives that you’re particularly excited about, and how do they build upon the themes and motifs present in your previous work?

I am currently working on lots of fun art commissions and collaborations with the likes of Pakistani luxury brand ‘Zara Shahjahan’. On the other end, I am expanding my ‘diaspora digest’ brand to tote bags, homeware and decor alongside art which I have spent the last year designing and curating and poured all my heart and architectural skills into. I am very excited about spreading beautiful pieces of our beloved culture around the world!

Looking ahead, what are your aspirations for the future of your artistic practice, and how do you envision your work continuing to evolve and resonate with audiences globally?

I would love to keep building on my work as a multidisciplinary creative! Keep making more art that reaches the world, expand my brand with products that touch the diaspora and keep my architectural work going at the same time through set design, furniture design, creative direction and concept work etc. while collaborating with brands and creatives that I look up.

In tracing her journey from an intended career in medicine to becoming a celebrated architect and designer, Areesha Khalid’s story is one of resilience, creativity, and cultural affirmation. Her work not only reflects a personal journey of self-discovery and acceptance but also contributes to a larger discourse on identity, representation, and the power of art in bridging cultural gaps. Through projects like ‘Diaspora Digest’ and ‘Hacienda for Homo Ludens,’ she challenges traditional boundaries and offers new perspectives on what it means to create and inhabit space. Her future endeavours promise to continue this trajectory of innovation and cultural celebration, inspiring audiences around the world to see the beauty in their own identities and histories.