In the realm of architectural conservation and heritage preservation, Abha Narain Lambah stands as a luminary, weaving a narrative that seamlessly blends the past with the present. With a career spanning over two decades, her work transcends conventional boundaries, encompassing not only the meticulous restoration of iconic structures but also a profound commitment to community engagement and the delicate dance of adaptive reuse. As an architect, conservationist, and storyteller, Lambah’s influence extends far beyond blueprints and structures, touching on the very essence of cultural identity and community well-being.

Join us on this architectural odyssey as we delve into the intricate world of heritage preservation with Abha Narain Lambah. From the bustling streets of Mumbai to the serene landscapes of Kashmir, each project tells a tale of dedication, challenges conquered, and a relentless pursuit of honouring the past while embracing the future.

Foyer: To begin, could you provide insights into significant projects that have shaped your career in heritage architecture? Please elaborate on the challenges you faced during these endeavours.

Abha Narain Lambah: Over the past 25 years, my journey has been quite unconventional in comparison to many architects. Typically, individuals begin their careers with residential projects, but my initiation involved a comprehensive undertaking—the signage and regulations for Dadambhai Naoroji Road, a historic and bustling commercial spine in Mumbai. Subsequently, I embarked on the restoration of Elphinstone College, a prominent public building and one of the oldest educational institutions. This restoration was initiated through a citizens’ movement during the Kala Ghoda Festival.

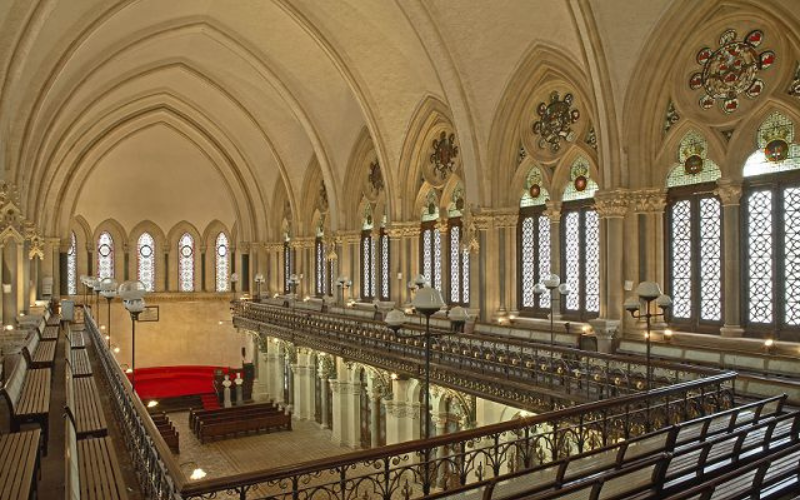

Unlike the common trajectory in architectural practices, my career unfolded inversely, commencing with projects of public significance. My focus shifted towards citizen-initiated urban conservation endeavours, such as those in Kala Ghoda or Horniman Circle in Mumbai, where I contributed to developing urban guidelines for Ballard Estate. My trajectory evolved into the preservation of non-monumental historic buildings across both rural and urban landscapes. India boasts a remarkable spectrum of 6000 years of built heritage, but governmental policies typically safeguard only a select few, leaving a vast array of historic structures without protection. In the absence of funding for buildings beyond nationally protected monuments, my practice has often entailed advocacy and professional consultancy. The past 25 years have seen a range of projects, from restoring the oldest railway station, Byculla Station, solely through citizens’ efforts to revitalizing synagogues and Jewish heritage libraries with a combination of citizen and corporate sponsorship. We have also undertaken pilot projects, such as urban illumination for night tourism in the walled city of Jaipur and contributing to the heritage of Srinagar Smart City.

Our commitment extends to experimenting with the design of new structures within historic contexts. For instance, the design of the new Darbar Hall and Secretariat in the historic precinct of Raj Bhavan, Mumbai, explores what contemporary architecture should look like in such settings. Another notable project involved creating a modern, largely underground structure at the Balasahab Thackeray on Rashtriya Smarak within the historic precinct of the Mayor’s Bungalow, ensuring sustainability and minimal environmental impact. All in all, my practice believes in designing with a deep respect for heritage, promoting sustainability, and offering design solutions that maintain a delicate balance between tradition and modern sensibilities.

F: Your career has taken quite a turn, focusing on people and community-centric projects for the past 25 years. Can you share the vibe or impact you aim to create when diving into these collaborative endeavours?

ANL: Absolutely. In my line of work, I often find myself navigating through urban and community spaces. Unlike traditional projects with a single client, I deal with larger communities, like the 350 shopkeepers in Wall City, Jaipur, or a mix of stakeholders from banks to luggage shops on Dadabhai Naoroji Road. Working on urban projects means not just serving as a mediator for community needs but also designing with a broader responsibility to represent the city or village.

It’s not just about satisfying the immediate client by cutting the check; it’s about understanding and catering to the needs of the entire community. This involves lots of discussions, whether it’s hashing out deals with shopkeepers or connecting with village communities in places like Hampi. I think it’s a crucial aspect of architecture, especially when it comes to designing public spaces – making sure our designs resonate positively with the diverse communities they serve.

F: Clearly, your practice is deeply rooted in serving the people in every possible way. Shifting gears a bit, could you share your approach to maintaining a delicate balance between preserving a building’s historical authenticity and integrating modern preservation techniques? Perhaps you could illustrate this with an example from your work.

ANL: Absolutely. Conservation is a broad field covering restoration, preservation, and adaptive reuse. Every case is unique, but the essence lies in maintaining authenticity and the spirit of the place. Take, for instance, the Ajanta Caves, a World Heritage Site. Here, authenticity is paramount, but we also need to balance the needs of visitors, addressing concerns like universal accessibility and risk management.

In contrast, let’s look at the Opera House. Besides the urgency of restoring a building on the verge of dilapidation, we had to make it relevant to 21st-century visitors. This meant introducing modern amenities like air conditioning, top-notch MEP services, and international-level acoustics. The challenge lies in harmonizing the contemporary needs of today’s audience with the intrinsic spirit of the place, ensuring that one doesn’t overshadow the other. It’s a delicate dance of blending the new with the old, preserving identity and the spirit of the location.

F: Delving into the preservation process, what methods do you employ to thoroughly research and grasp the historical and cultural context of a structure before initiating a project? And how does this extensive research shape your overall approach?

ANL: See, research is the backbone of any effective conservation project. It involves a multi-faceted approach, including archival research, photographic documentation, and sometimes utilizing advanced technologies like LIDAR and photogrammetry. This extensive research serves as the initial groundwork for any project. Without a solid understanding of a building’s original intent, materials, and design, it wouldn’t be prudent to intervene. So, this homework becomes the foundation for every project we undertake. It’s about uncovering the historical layers, understanding the cultural significance, and gaining insights into the original design intent. Only then can we approach the preservation or restoration process in a way that truly respects and honours the structure’s heritage.

F: Transitioning into the role of heritage architecture, how do you believe it specifically contributes to preserving cultural identity and fostering a sense of community? And in what ways do your projects embody these principles?

ANL: Heritage architecture, in my view, is one of the most tangible means of preserving the identity of a region or a community. It seeks to extend the lifespan of iconic markers that define the identity of a nation, community, or region. Conservation, therefore, plays a crucial role in safeguarding the beliefs and cultural landscape of a region by preserving its historic buildings, pilgrimage routes, or urban landscapes. This process allows for the authentic transmission of ideas from one generation to the next in a tangible and meaningful format.

F: We’ve been discussing various aspects of conservation and your pivotal role in it, not only in Bombay but across India. I’m curious when you started your career, did you initially aspire to work on residential projects as opposed to conservation endeavours? If so, how did your perspective evolve? Did you ever contemplate going back to residential projects, and what was your thought process around that?

ANL: When I graduated 30 years ago in 1993 from the School of Planning and Architecture, there were few female graduates, and architecture was predominantly a male-dominated field. I consciously steered away from interiors and residential projects, aiming to avoid being pigeonholed. Instead, I took on projects that defied conventional expectations for a woman architect. Over the past 25 years, we’ve adhered to this approach. Now, perhaps it’s time for us to explore the realm of interiors and residential buildings, expanding our horizons beyond the conservation-focused projects that have been our mainstay.

F: Reflecting on the past 30 years, how do you perceive the changing landscape for female architects entering the field? Have you observed a shift in perception, and if so, what factors do you think have contributed to this change?

ANL: I don’t believe there should be a distinction in design based on gender; it’s more about individual design journeys.

F: Absolutely

ANL: However, when looking at the architectural landscape over the past 30 years, there’s still a noticeable scarcity of women-led practices. Hopefully, in the coming decades, we’ll see more, but currently, it remains on the fringe with very few female-led architectural practices.

F: Who would be your top three favourite women-led practices in India and globally?

ANL: I’ve always admired Gae Aulenti, who led projects like the Asian Museum and La Fenice Theatre. Lina Bo Bardi is another standout figure, though not discussed enough. Within the subcontinent, Revathi Kamat is my teacher and a significant figure in women-led practices. Meena Mani, one of my initial bosses at Stein Doshi Practice, also played a crucial role in encouraging women architects to pursue and thrive in the profession. Each of these women has been instrumental in paving the way for others in the field.

F: And they’ve all done some truly iconic work . We believe that collaboration with various professionals is considered crucial in heritage architecture. Could you share how your collaboration with historians, engineers, and experts from different fields contributes to the success of your preservation initiatives? How do these diverse perspectives come together for the greater good of a project?

ANL: In the realm of conservation, each project comes with its unique demands, often necessitating collaboration with professionals from various disciplines to harness all available resources. For instance, in the restoration of the Royal Bombay Opera House, we closely collaborated with Richard Noel, a UK-based acoustician. Engaging with acoustic consultants and lighting designers was crucial in recreating the authentic ambience of an opera house.

On urban projects, we’ve partnered with lighting consultants and designers to enhance the overall visual experience. In archaeological projects, individuals like Dr. John Kipkar and Dr. Sooraj have been invaluable collaborators, offering expertise related to ancient sites. Our collaborations extend to material conservators, stained glass conservators like Anupam Shah and Swati Chandgadkar, textile restorers, and photography conservators, amongst others. Each collaboration brings a unique perspective, enriching not only the project but the entire team. The exchange of ideas and learning from one another significantly enhance the design process. It’s a collective effort where diverse expertise comes together to ensure the success and authenticity of each preservation initiative.

F: If you weren’t a heritage conservationist, what do you think you’d be doing with your life? Our hunch would be a historian, but I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

ANL: Well, at one point, I considered studying architectural criticism. Had I not pursued architecture, I would have had a strong interest in joining the foreign service. In both scenarios, it seems like I would have found myself travelling to exotic locations.

F: It sounds like travel plays a significant role in your life and work. Would you say that’s true?

ANL: Absolutely. I have a deep love for travel and exploring new cultures and sites. Even now, I find myself travelling 2 to 3 days a week. And every three months, I make sure to take a short vacation. It helps me recharge, refocus, and reboot before diving back into work.

F: When you embark on your travels, what’s your process like? Do you actively seek inspiration from your surroundings, or is it more of a subconscious absorption of colours, materials, and ideas? How does travel influence your creative process?

ANL: For me, travel doesn’t necessarily lead to an immediate translation of inspiration. It’s a subliminal process where you subconsciously absorb colours, materials, and ideas. It’s not a linear journey, and sometimes you find yourself recalling a memory or an image from years ago while sitting at your computer. It’s not necessary that the destination directly correlate with the project I’m working on. However, for me, it’s a way to step away from it all, distance myself from the immediate work environment, and simply recharge. So, indeed, it serves as a breather and a source of rejuvenation for me.

F: What is your guiding philosophy regarding the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings? And how do you ensure that the new purpose aligns with the building’s historical significance and value?

ANL: The very act of adaptively reusing a structure is, in itself, an extension of its life, preventing it from falling into disrepair and disuse. However, it’s crucial to ensure that this extension aligns with the building’s essence and historical significance. The new purpose cannot conflict with the principles that define the building. Finding compatible uses is key, even if the new purpose is drastically different, such as transforming a railway station into a museum. It must still be respectful of the building’s structure and essence. Striking a balance is essential, and a good designer should avoid being heavy-handed in their approach. Two fundamental rules guide this process: thorough research to understand the building and maintaining a delicate balance where neither the old nor the new overpowers the other. These principles are integral to the approach taken in heritage conservation initiatives.

F: You’ve mentioned working across different types of structures; are there certain strategies or tactics that remain consistent across all your projects, or do they vary based on the specific requirements of each project?

ANL: The two fundamental principles I mentioned earlier—understanding the building and ensuring that the new use is respectful—will always be consistent. However, the applications can be entirely divergent. For example, transforming a cinema hall into an opera house or converting a bus stand into an art centre. Currently, we’re working on repurposing an old PWD building into a cultural complex in Goa. The only constant is questioning whether we are respecting what we’ve been handed.

F: It seems like respect is a crucial aspect of every project you undertake.

ANL: Absolutely. Respect forms the foundation of every project, ensuring that the essence and historical significance of the structure are preserved and honoured in the adaptive reuse process.

F: Returning to community engagement, what methods do you and your team employ to involve residents and stakeholders in the decision-making process for the projects you undertake?

ANL: Our outreach methods have been diverse. I’ve gone door-to-door in Jaipur, sharing giant samosas at every shop to discuss the lighting up of Jaipur’s streetscape. When working on the Jaipur metro, which was underground and met with scepticism, we created a film and played it publicly in areas like Johri Bazaar to address residents’ concerns and ensure their support.

Our outreach strategies span from creating press notes to producing films and documentaries for information dissemination. This includes personal meetings with villagers, participation in local village meetings, and conversations in the dark with residents. It’s been a mix of informative sessions, films, and indulging in local treats like sugary chai and lassis to foster community understanding and involvement.

F: It sounds like a flavorful and engaging approach to your work. Shifting gears a bit, in your multifaceted roles as an artist, architect, conservationist, storyteller, and more, is there one word, if any, that you would use to describe yourself?

ANL: Architect. I see myself as an architect because, like a music composer, an architect has to consider different fields and disciplines and coordinate them together in a harmonious composition.

F: In the realm of heritage preservation, facing complex legal and bureaucratic challenges is common. Can you share experiences where you successfully navigated these obstacles, highlighting the strategies that proved effective in the long run?

ANL: Let’s consider Mumbai. Heritage regulations were already in place by 1995, but a public interest lawsuit was filed against billboards and hoardings in heritage precincts by Dr. Anahita Pandole. I went from building to building, creating a list and providing justifications to the High Court of Bombay and Maharashtra, explaining why each billboard should be removed. Detailed interventions like this are sometimes necessary. While working on the UNESCO nomination dossier, we had to balance the management plan to explain how the UNESCO nomination would impact the future of these areas and developmental policies. Deep diving into regulations and development controls is often necessary to work on a policy level.

F: Out of all these incredible projects, is there one that has been particularly close to your heart?

ANL: There are too many, as I deeply get involved in all my projects. It’s challenging for me to pick just one.

F: Can you provide more details about your involvement in the restoration work at Shalimar Bagh in Kashmir? What were the unique challenges you faced, and how did you address them?

ANL: Shalimar Bagh holds special significance for me as my grandfather was a botanist in Kashmir in the 1930s, and my family has deep connections and memories associated with the place. In 2020, I was appointed by the Jammu and Kashmir Government to prepare the nomination dossier for UNESCO World Heritage Site status for all the Mughal Gardens of Kashmir. This process took two years.

To create a pilot model project for garden restoration, I approached the JSW Foundation. With their financial aid, we are currently working on restoring Chandanwari Bagh. It’s an ongoing project that will take about a year and a half to complete.

F: Thank you so much for sharing these insights. It’s been a truly enlightening conversation.

As we draw the curtains on this enlightening conversation with Abha Narain Lambah, we find ourselves enriched by the resonance of architectural wisdom and cultural stewardship. Through the intricacies of heritage preservation, Lambah has not only restored physical structures but also rekindled the spirit of communities, fostering a sense of identity and pride. The architectural tapestry she has woven reflects not merely bricks and mortar but the profound intertwining of history, culture, and community. Abha Narain Lambah’s journey transcends the mere restoration of buildings; it is a testament to the enduring power of architecture to shape narratives, connect generations, and leave an indelible mark on the cultural landscape.

As we step away from this exploration, we carry with us the echoes of stories told through architectural forms, the commitment to community engagement, and the unwavering dedication to preserving the heritage that binds us all. Abha Narain Lambah’s legacy is not confined to structures; it is etched in the collective memory of communities she has touched, forever echoing the harmonious blend of the past and the present.